For almost a decade the British intelligence services were compromised by a deeply damaging and ultimately futile hunt for the Soviet enemy not just within its own ranks but in government, the Civil Service, in business and academia too. It was sparked by the defection of former MI6 officer Kim Philby to Moscow in 1963. Forced out of MI6 after the defection of his friends, Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean, more than ten years before, he had been named as a spy in parliament and the papers. In spite of Philby’s public denials, senior counter espionage officers in MI5 were convinced he was a double: How had he managed to get away with it for so long? Was he protected by an agent at the very top of British intelligence?

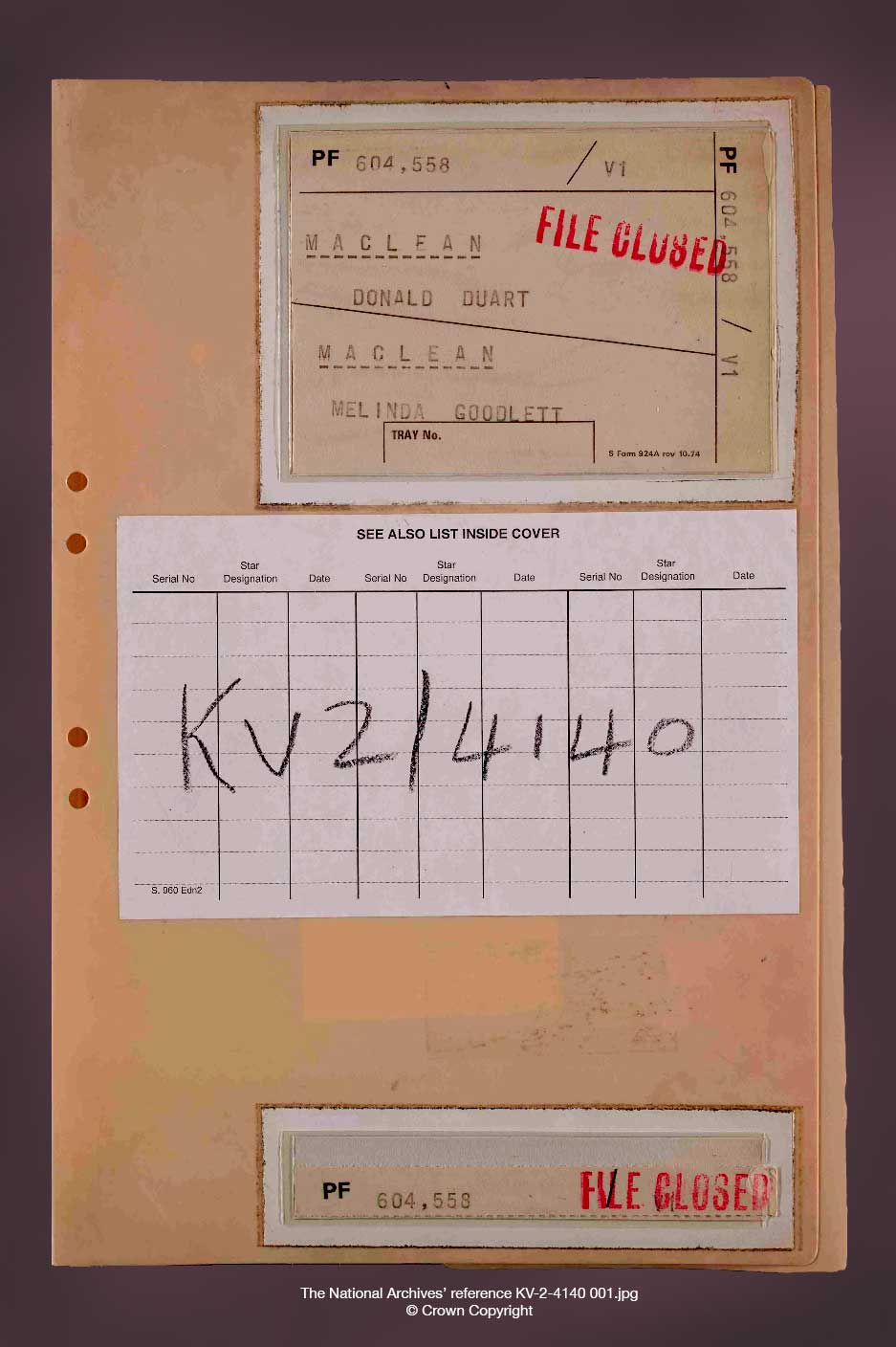

MI5 file on Donald Maclean.

On 7th March 1963 the head of the Soviet counter-espionage section at MI5, Arthur Martin, met Director General, Sir Roger Hollis, to warn of a serious penetration of the Service. The chief suspect, he said, was no less a figure than Hollis’ deputy, Graham Mitchell. One piece of information he chose to withhold from his boss: he had another candidate. Martin had already shared the name with the Chief of MI6, Sir Dick White, and outlined his conspiracy theory: Philby was tipped off by someone at the top of MI5. If it wasn’t the Deputy D.G., Mitchell, then it was Sir Roger, the D.G. himself, he said. Remarkably, White was prepared to take his claim seriously.

Martin and his successor, Peter Wright, could count not only on White’s backing but also the support of the CIA. The Agency’s counter-intelligence chief, James Angleton, had begun his own trawl for double agents. A master spy in British intelligence was entirely consistent with his grand conspiracy theory that the West was being subverted by networks of Soviet spies on both sides of the Atlantic. Dick White wanted ‘to get to the bottom of the problem’, an MI6 officer later recalled. ‘He was an enthusiastic supporter of Angleton’s investigation’, and of his disciples, Wright and Martin.

By the summer of 1964 all pretence had gone; the Director General of MI5 was under investigation too. Hollis was forced to bow to pressure for a comprehensive enquiry. It was to be conducted by a working party made up of both MI5 and MI6 officers, chaired by Peter Wright, and it was given the code name FLUENCY. Hollis was chief suspect, Mitchell remained a suspect, other senior officers including a future D.G. were named as suspects, and parallel investigations were begun into former Communist Party members and their associates in government, parliament, the civil service, the military and academia. Hundreds of persons ‘of interest’ were investigated including the Prime Minister, Harold Wilson. FLUENCY became a witch hunt. James Angleton exercised a controlling influence over the working party to the end, even though he was unable to furnish it with any convincing evidence.

The authorised history of MI5 describes the FLUENCY investigation as ‘the most traumatic episode’ in the Cold War history of the Service, one that seriously compromised its efficiency and morale.