Ways To Make History Talk by Andrew Williams

The Scotsman, 31 January 2009

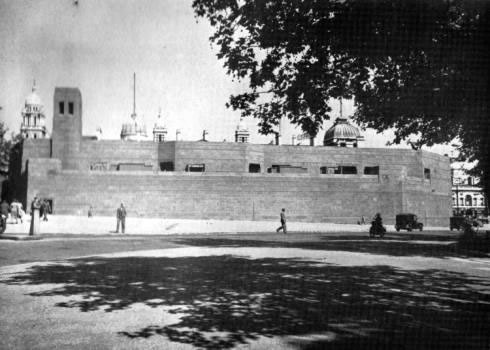

IT MAY HAVE BEEN A LINE IN A secret report on British naval codes in the Second World War, or an unguarded remark by a veteran who admitted giving too much to his interrogator. Pulling at the tapestry of the story after so many months, it is hard to disentangle the threads that led me to The Interrogator. But perhaps it began with an extraordinary building, an enormous filthy grey concrete bunker a stone’s throw from 10 Downing Street, a building many thousands of Londoners pass every week without noticing – the Citadel. It’s a little like a submarine with its squat tower on the Mall and a concrete deck stretching to Horse Guards Parade – to coin a phrase, a monstrous carbuncle on the elegant face of Whitehall and government.

The Citadel. Naval intelligence’s secret operational intelligence centre at the corner of Horse Guards Parade, London. 1941

I often passed it before I moved to Edinburgh and wondered why it was there and what its story could be. Then, in the course of a BBC TV series I was making on the Second World War, I came across a reference to the Citadel in the memoirs of a former member of naval intelligence and, little by little, I began to lift the veil on its secret history.

Built in 1941 for the Royal Navy’s intelligence division, the secret battle against the German U-boat was waged in its sub-basement. The concrete was still wet when, in February that year, Hitler promised a Nazi rally that Britain’s lifeline of food and raw materials from America would be cut by his “grey U-boat wolves”.

In this secret Citadel intelligence from agents, air reconnaissance, decoded enemy signals – 15 different sources – was gathered and pressed into place like the pieces in an enormous jigsaw of the enemy’s operations in the Atlantic. Above all, it was vital to find and track his submarines in time to save the convoys and cargoes that made up the country’s lifeline to America. And when the intelligence dried up, the small team of officers who studied the enemy’s movements hour by hour – lawyers, academics, journalists in civilian life – was asked to predict his movements. If they got it wrong, ships were sunk, men drowned and the country’s survival hung in the balance.

The secret war against the U-boat, fought in the Citadel’s sub-basement, fascinated me. Few accounts have been written of what happened here but while researching the TV series I came across an extraordinary document in the National Archive in London – a colourful and touching memoir by a young Scottish academic called Margaret Stewart, the only woman to work as a senior intelligence officer in the Citadel. From the pages of this memoir my feisty heroine, Mary Henderson, was born and the story of her life in the Citadel began to take shape, a story of love, conflicting loyalties and final betrayal.

And from reading the same set of declassified intelligence documents, I pulled another thread. It became clear vital intelligence from captured U-boat crews had been neglected by the navy and it had cost the country ships and men.

For most in the Citadel, the enemy was a cardboard arrow on a map table but for a small section of naval intelligence – its interrogators – the enemy had a face, a name and a history, and locked inside him were secrets that would help win the battle in the Atlantic. The interrogator’s story: war fought face to face across a table, hour after hour in a bare room, the struggle to win your enemy’s confidence, to tease what you need to know from him, to trick him, bully him, and finally break him. “A breaker is born not made,” one senior interrogator wrote after the war. “Perhaps he is recruited from the concentration camps, where he has suffered for years, where, above all he has watched and learnt in bitterness every move in the game.”

I was fascinated by this “game”, the war across the table, and I spoke to former naval interrogators and read the secret reports they had written at the time. Sixty years on, they still remembered, with resentment, how, in the first years of the war, the intelligence they had wrung from U-boat prisoners was undervalued or ignored.

And it was a U-boat officer who, in an unguarded moment, lifted the lid for me on how costly this failure proved to be. After months of wooing, the former first officer of Germany’s must successful U-boat – a submarine responsible for sinking 38 British ships – agreed to meet me. In the course of our conversation, he let slip that he had been tricked into giving too much information to British interrogators after being captured in March 1941, but he refused to say more. A search through intelligence files at the National Archive brought to light the short transcript of a conversation between two prisoners. It had been picked up by a hidden microphone and secretly recorded. In it, the first officer of U-99 suggests the extraordinary success of his U-boat and the other German submarines in the Atlantic owed much to a catastrophic intelligence failure on the part of the British – the navy’s codes had been broken. No-one seems to have acted on this extraordinary intelligence.

Little by little the story came together, a story I needed to tell. The Germans had penetrated our naval codes and were able to direct their U-boats to our convoys. For years, the story had been almost lost as historians concentrated on the success of Bletchley Park in breaking the German Enigma codes. But this was a different, shameful story. A secret investigation by naval intelligence after the war concluded the failure of the country’s naval codes “very nearly lost us the war”.

That was my story and a hero began to take shape – a damaged hero, an interrogator, a “breaker” who had suffered and in bitterness learned the game. His challenge was to convince his superiors that a catastrophic intelligence failure was taking the country to the brink of defeat: the Interrogator.