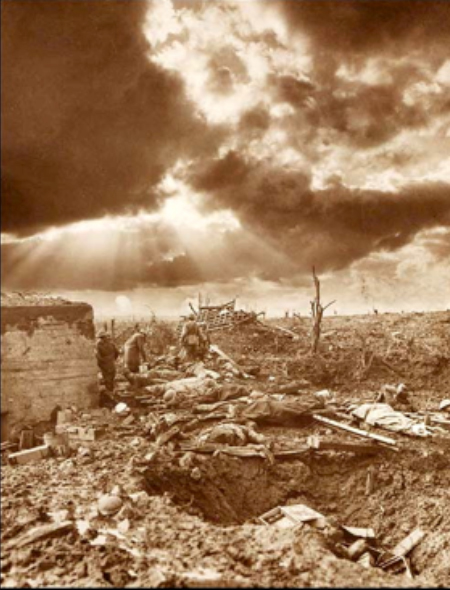

‘I died in hell, they called it Passchendaele’, the poet, Siegfried Sassoon, wrote of the battle that for many represents the senselessness of trench warfare and the waste of lives. Canadians captured the ruins of Passchendaele on November 6th 1917, after more than three months of fighting.

‘The buildings had been pounded and mixed with the earth, and the shell exploded bodies were so thickly strewn that a fellow couldn’t step without stepping on corruption’, one of their number reported. ‘Our opponents were fighting a rear guard action which resulted in a massacre for both sides.’

Haig had assured the British prime minister and his cabinet colleagues the summer before that the Germans were exhausted and ‘final victory’ was ‘within reach this year’. His plan was to capture the high ground around the town of Ypres and then press on to the Belgian coast. Passchendaele was one of his first objectives. ‘Fantastic and dangerous’, was the French view of Haig’s plan, because three years of war had taught them the futility of ‘aiming at a distant objective’. But Haig was encouraged by Charteris’ intelligence reports to believe that a knock out blow was still possible.

Haig handed the command of his great offensive to another optimist. General Herbert Gough’ s only real qualification for the task was that he shared his commander-in-chief’s belief in the ‘hurroosh’ – the rapid advance – but by appointing a general of limited experience Haig was able to ensure his wishes were carried out to the full.

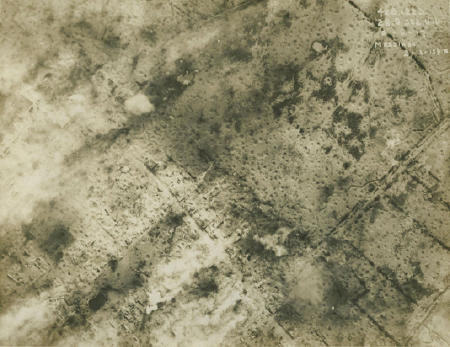

Passchendaele or 3rd Ypres, to give the campaign its proper name, was not one battle but a series. It began with a large preliminary attack on the Messines Ridge, south of Ypres. On 7th June 1917, nineteen enormous mines were detonated beneath the German line. The muffled roar was heard in London.

Aerial photograph of Messines Ridge

‘The trenches were now the graves of our infantry’, one German eyewitness reported. In the fighting that followed British forces advanced three thousand yards to capture high ground in the south of the Ypres salient. It was a notable success and a lesson in what might be achieved with thorough preparation and a limited objective.

The battle proper began a month later with the usual lengthy bombardment. In parts of the line it was to prove no more effective than it had on the Somme the summer before.

Marked in blue, the British advance at Ypres from July to November 1917

Zero Hour: 3.50 a.m. July 31st: British soldiers clambered over the top in darkness. During the course of the first day the British left and centre overran the first two German lines and advanced 3000 yards. By the standards of the Western Front it was a major success. But on the right, the British struggled to make head way against the enemy’s heavily defended positions on the Gheluvelt Plateau. Failure to capture the plateau left the centre and left of Haig’s line vulnerable to enfilade fire from the enemy’s artillery.

The assault on July 31st was to set the pattern for the next three months. Stiff German resistance, counter bombardment and counter attack, might have suggested to a more astute commander-in-chief that the enemy was by no means crumbling. To make matters worse, the very poor weather turned low lying areas of the battlefield into a quagmire. After only a week of fighting the shell holes were full of water. ‘Every place is in full view of the enemy’, a sergeant of the Ulster Division wrote in his diary. ‘There is neither the appearance of a road or path and it requires six men to every stretcher, two of these being constantly employed helping the others out of the holes; the mud in some cases is up to our waists. A couple of journeys… and the strongest men are read to collapse.’ The situation was to become immeasurably worse.

Gough sought to give his commander-in-chief his breakthrough by renewing the attack on the 10th of August, on the 16th and on the 19th. ‘If we keep up our effort’, Haig told his commanders on the 19th, ‘final victory may be won in December’ – but by the end of the month he had lost patience with Gough.

The axis of the British attack shifted to the high ground in the south of the Ypres salient. There would be a new plan and a new commander: General Plumer of Second Army.

The battle of The Menin Road began with a preliminary bombardment of 1.6 million shells. During the night of September 19th 65,000 men moved into position. They attacked in the rain the following morning and drove the enemy back an average of 1250 yards along the line. After the disappointments of August, GHQ had something to celebrate. In seven weeks of fighting the British had succeeded in advancing three and a half miles at a cost of 86,000 casualties, but now Haig proposed a further advance of three and a half miles in just one or two weeks.

The British attack resumed on September 26th at Polygon Wood, and again at Broodseinde on the 4th of October. Plumer’s plan was to advance in small steps, with ‘bite and hold’ operations. Haig envisaged something altogether more ambitious. Remarkably, the commander-in-chief was still talking of a decisive breakthrough to the Belgian coast thirty miles away. He ordered the cavalry up to support a rapid advance.

It began to rain five days before the next attack at Poelcappelle, and it rained without ceasing. Supplies could not reach the front, men and pack animals that stepped from the duckboard tracks were lost to the mud, and those who did make it into the line were exhausted. The artillery was short of shells and the softness of the ground denied a stable platform for the guns. Their crews were firing blind because aerial reconnaissance was impossible. Meanwhile, the Germans had reinforced their own artillery and were increasing the concentration of their fire on British forward and reserve positions.

The British and Australians attacked on the 9th of October. They made little or no progress. Haig was still determined to fight, and assured the French President that ‘the enemy is now much weakened’ and ‘lacks the desire to fight’. The battle resumed three days later. The infantry rose without the protection of artillery and struggled forwards under intense fire. ‘Surely one of the lowest points in the British exercise of command’, the historians Wilson and Prior note in their study of the battle, Passchendaele: The Untold Story. The Belgian coast had become Haig’s obsession, and thousands of men had already paid for it with their lives.

By the 12th of October the British failure was evident to all. The man who bore great responsibility for the false hopes, Charteris, noted in his diary; ‘it is the weather and the ground that we are fighting now. We have beaten the Germans, but winter is very close and there is now no chance of getting through.’ Haig offered the same explanation to the prime minister and his cabinet colleagues. They had only approved the field marshal’s grand plan on the condition he brought it to a halt when casualties became intolerable. That point had been passed weeks before.

The final phase of the battle was for the Passchendaele Ridge. The task was given to the Canadian Corps. Its commander, General Currie, brought a sense of realism to the task. He insisted on two weeks preparation and the largest possible concentration of artillery. The Canadians would proceed in three steps of 500 yards, separated by five or six days – longer if necessary. It was a return to ‘bite and hold’. The push on the ridge began on October 26th with the first advance of 500 yards. The second attack was made on the 30th and the third attack on the 6th of November, when the Canadians captured the village of Passchendaele.

Currie’s steps had delivered a symbolic victory at the cost of 12,000 Canadian casualties. Total British and Dominion casualties including Messines, numbered 275,000 men, of whom 70,000 lost their lives in the campaign. Wilson and Prior estimate that the total fighting strength of Haig’s force in France and Belgium was reduced by between 10 and 12 divisions out of a total strength of 60. Germany suffered a little under 200,000 casualties. At the same time, German divisions were beginning to transfer from the Eastern Front to the West.

British failure at Ypres seriously damaged the morale of those who would be called upon to meet the German challenge in 1918. Charteris’ false intelligence encouraged Haig and his generals to believe the final victory was possible by December, but the blame does not rest with him alone. Haig wanted to believe. By the summer of 1917 the British army was capable of delivering a series of devastating ‘bite and hold’ blows on the enemy, but Haig was still wedded to the idea of a big breakthrough to end the war at something like a stroke. Britain’s politicians were at fault too. They could have insisted Haig honour his pledge to stop when it became clear his breakthrough was not possible.