| > Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig | > General Sir James Marshall-Cornwall |

| > Brigadier John Charteris | > General Sir Stewart Graham Menzies |

| > Captain Sir Mansfield Smith-Cumming | > Elsbeth Schragmüller |

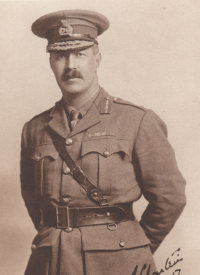

Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig

Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig

Many people still think of Haig as a ‘butcher’ and ‘blunderer’, and they blame him for the terrible loss of British and Empire lives on the Western Front. Academic champions of the field marshal have written of ‘a great captain’, of a ‘master of the field’, and of ‘the educated soldier’. But the scholarly consensus perhaps is of a man with a stoic sense of duty and of his own destiny. Not a military genius, but, in the words of Winston Churchill, a man possessed of ‘an exceptional greatness of character’. For nearly three years of war he shouldered the burden of command in the west. The responsibility would have broken a less determined and stubbornly optimistic commander. He was reserved in company and uncomfortable with shows of feeling, but he was not without sympathy for the ordinary soldier. Could another British commander have done a better job? Prime Minister, Lloyd George, sent a delegation to France to find one, but it came back without a realistic alternative. There were better generals perhaps, but Lloyd George’s delegation found no one more suitable to shoulder the burden of commanding the entire British Expeditionary Force.

To the end of his life, Haig viewed the long hard slog at Passchendaele as a necessary post on the road to final victory. But not even his most enthusiastic defenders are willing to travel with him so far. His critics suggest that nothing illustrates his limitations as a commander better than the obduracy he showed in fighting on in the mud of October and November when a breakthrough was quite impossible.

Haig makes two short appearances in ‘The Suicide Club’, but his influence on GHQ Staff – his personality – is my larger story.

Brigadier John Charteris

Brigadier John Charteris

Haig’s head of intelligence at GHQ and a fellow Scotsman, he was ‘a sapper of bulky build, cheerful temperament and nimble brain’, to quote one of his subordinates. Although he was intellectually well equipped for the role of head of intelligence, he did not have the integrity necessary to speak the truth without fear or favour. Disliked by Haig’s senior commanders, distrusted by his own staff, he was generally considered to be ‘incredibly bad’. One senior intelligence officer at GHQ observed, ‘his breezy and optimistic nature’ seemed to ‘act like a tonic on his slow-thinking but honest-minded Chief’. Charteris’ intelligence summaries were written to bolster morale rather than to paint a true picture of the enemy’s capabilities. Haig seems to have had some inkling that this was the case. Perhaps he was ready to accept a partial truth so he could to offer the same to the country’s politicians. Charteris noted on more than one occasion that ‘the Chief’ went further in his optimistic claims to Cabinet ministers than the facts could honestly support. ‘What an amazing mentality!’ General Wilson wrote of Haig in his diary in 1917. ‘And I attribute most of this to that fool Charteris.’

Captain Sir Mansfield Smith-Cumming RN [1859-1923]

Captain Sir Mansfield Smith-Cumming

The founding father of Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service. His Agents called him C – he referred to them as his ‘scallywags’. In 1909 he was drawn from the naval backwater of harbour defence and given responsibility for building an espionage network for the newly established Secret Service Bureau. Punch-like, with angular features and keen grey eyes, he glared at recruits to the new service through a gold rimmed monocle, but as one of them later recalled, ‘the Chief’ inspired ‘feelings of deepest personal admiration and affection’ in those who worked for him.

General Sir James Marshall-Cornwall

General Sir James Marshall-Cornwall

Army officer, linguist, historian, and the inspiration for Major Marshall in The Suicide Club. At the outbreak of war, Marshall-Cornwall transferred from the artillery to the new Intelligence Corps, ‘a formation of which I had never heard’. His sharp mind and facility with languages equipped him well for the work and he was posted to general headquarters in January 1916 with the rank of major. He quickly realised that the information offered to Field Marshal Haig by his head of intelligence, John Charteris, was based more on what he thought his chief would be pleased to hear than on a realistic assessment of the situation. A tempestuous two years at headquarters came to an end in January 1918, when he was transferred to the War Office. He continued to serve in the army after the war and rose to the rank of general.

General Sir Stewart Graham Menzies

General Sir Stewart Graham Menzies

For my character Major Graham, I drew on the career and personality of Major, later General Stewart Graham Menzies. Old Etonian scion of a Scots whisky family, his mother and step father were close to the royal family and a number of prominent politicians. In the first months of the war, Menzies was wounded and decorated for bravery by the King. Unfit for more frontline duty, he joined counter intelligence at GHQ. His biographer claims Menzies was the ‘whistle-blower’ who engineered Charteris’ dismissal in December 1917. After the war he joined the Secret Intelligence Service, rising through its ranks to become its chief in 1939. During World War 2, he expanded MI 6’s activities, and was responsible for supervising the code breaking activities at Bletchley Park. He finally stepped down from active service in 1952.

Elsbeth Schragmüller

Elsbeth Schragmüller

A favourite with movie makers, the fictional exploits of the German spy known as the Fräulein Doktor have ensured Schragmüller a celebrity matched only by Mata Hari. She first appeared to a wider public in the 1934 film, Stamboul Quest, and twice more before the Second World War. In fact very little is known about Schragmüller’s life and work. She acquired the epithet ‘Fräulein Doktor’ because she was one of the first women to take a doctorate at Freiburg University and work as a lecturer. When the war began she volunteered for service in the German military administration in Belgium. She impressed Major Nikolai of the General Staff’s intelligence department with her efficiency and in 1915 he put her in charge of one of the two sections at the Antwerp Kriegsnachrichten or war intelligence centre. Her responsibilities included the training of spies and counter espionage. After the war she returned to academia, her role as a spy chief a closely guarded secret.