‘I’ll come straight to the point’, she said, ‘the Prime Minister was a very poor man, now he’s got the whole Treasury of Great Britain behind him’. Her intentions were clear: blackmail. Pay up or her love affair with the P.M. was going to ‘blaze’ in the press. ‘He’s a very innocent man’, she observed to his intermediary; ‘he wrote to me – letters which were pornographic.’ The innocent in question – lest there be doubt – wasn’t Boris Johnson, it was Labour’s Ramsay MacDonald in 1929.

Ramsay MacDonald leaving Number 10 in 1931.

There have been fifty-five Prime Ministers since George I appointed Robert Walpole First Lord of the Treasury in 1721. Many have entertained mistresses, perhaps most – Number 10 has been home to notorious philanderers – solid Scots family man, Ramsay MacDonald wasn’t one of them. Within months of taking office his government was hit by the shockwave of the Wall Street Crash and a world economic crisis. Still handsome at 63, with wavy grey hair, a thick moustache, strong jaw and dark brown eyes, his beloved wife, Margaret, had died 18 years before, and he had brought up his four children alone. There had been other women, notably a secret fifteen year affair with another Margaret, a poet, society beauty, and daughter of an earl. Their love had foundered on the rock of his political ambition, on fear that the newspapers would make great sport of an illegitimate son of a ploughboy carrying on with an aristocrat. What would Labour’s working class supporters think?

Lady Margaret Sackville c.1900

At some point in the late 1920’s MacDonald met a Viennese lady, ‘a faded blonde, very sophisticated, very agreeable’ according to his friend, Sir Oswald Mosley. Notorious later as the leader of Britain’s Fascists, Mosley and his wife, Cynthia, were prominent Labour supporters at the time, and on the eve of the 1929 General Election Ramsay Mac invited them to join him at a hotel in Cornwall for a ‘gay party’. His ‘little Austrian friend’ – Frau Forster – was to be among the guests; ‘and being young people, and never thinking that people much older than ourselves could have love affairs, Cimmie and I thought nothing of it’, Mosley recalled.

By the autumn of 1929 the affair was over. Ramsay Mac was in Number 10, Mosley was at the Treasury, and Labour was in power but without a majority in parliament. Frau Forster was renting a flat in Horseferry Road – a poor district of London at the time – but only a few streets from Mosley’s grand house in Smith Square. In the account he gave his son, the writer, Nicholas Mosley, he claims Frau Forster telephoned to warn him ‘the government may fall’, and to request a meeting. She had visited Number 10 already, he discovered, and had spoken to the Prime Minister in the Cabinet Room. ‘I told him I had to get some money’, she said, ‘and he became completely hysterical and began to bang his head against the wall.’ MacDonald’s daughter, Ishbel, had entered and discovered him in a state. ‘Then he took me by the shoulders and pushed me out in front of all the porters in Downing Street,’ Frau Forster recalled. She had stumbled, fallen, broken a pair of glasses hanging from a chain, and a Downing Street policeman had picked her up and placed her in a cab. Mosley said he was shocked and she should understand that the Prime Minister was overworked and under terrible strain. But Frau Forster wasn’t interested in excuses; she had letters and she was willing to sell them. What was MacDonald to do?

‘Publish and be damned’, an illustrious predecessor, the Duke of Wellington, is reputed to have said when a famous courtesan threatened to reveal details of their relationship. Ten years later, in the 1830s, Queen Victoria’s favourite Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne refused to be blackmailed by the husband of his friend, Caroline Norton. In the court case that followed Norton’s husband sued Melbourne for ‘criminal conversation’ – adultery – and presented letters and stains on his wife’s clothes in evidence. The jury was unconvinced and threw out the case. Melbourne was adamant to the end of his life that the charge was false, but his private life was problematic nonetheless, in particular his predilection for whipping the orphan girls he took into his household as objects of charity.

Lithograph cartoon of Caroline Norton with her pet lamb, Lord Melbourne, watched by her ‘sheepish’ husband.

For the most part Queen Victoria’s prime ministers were more circumspect about their private lives than their eighteenth century predecessors; Melbourne’s brother-in-law, Lord Palmerston, was an exception. His reputation as a womaniser earned him the enmity of the Queen, who was shocked to learn ‘Lord Cupid’ had tried to force himself upon one of her ladies in waiting. While he was in office he was cited in a divorce case brought by a journalist called O’Kane who accused him of committing adultery with his wife. The case was eventually withdrawn, but the coverage in the newspapers boosted his popularity: Palmerston was 78 at the time. ‘She may be Kane but is he Abel?’ was the cry in the London music halls.

Lord Palmerston addressing House of Commons 1860

The ‘grand old man’ of Victorian politics, William Ewart Gladstone, was blackmailed too. Gladstone walked the street of London at night searching for prostitutes to save. ‘Rescue work became not merely a duty but a craving’, according to his biographer, H.C.G. Matthew. ‘It was an exposure to sexual stimulation which Gladstone felt he must both undergo and overcome.’ To counter the excitement he felt in their company he scourged himself with a whip, carefully marking each occasion in his diary. Inevitably his charitable work attracted the wrong sort of attention, and in 1853 an unemployed commercial traveller observed him talking to a prostitute and attempted to blackmail him. Gladstone reported the incident to the police and appeared in court to give evidence against him. The blackmailer was sent down for twelve months hard labour.

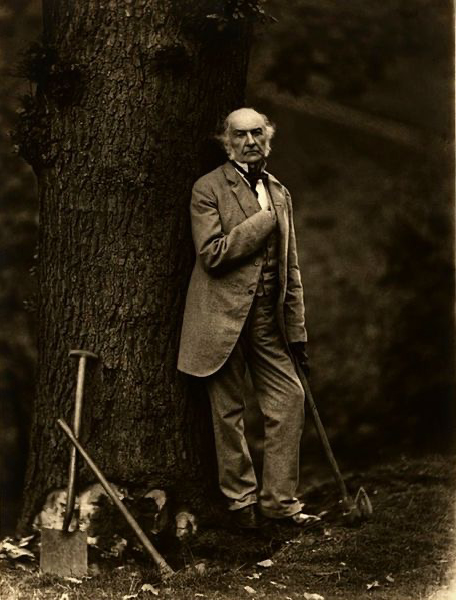

William Ewart Gladstone in 1887

Liberal Party colleagues continued to question the wisdom of his night time forays, nevertheless. In February 1882 two of his ministers tossed a coin to decide who would have the unenviable task of raising the matter with their chief. Another attempt was made by Gladstone’s secretary three months later, again without success; and in 1884 he was warned that a Downing Street policeman might sell a story to a newspaper. Not to be deterred, the Prime Minister ventured out on to the streets at night well into his eighties.

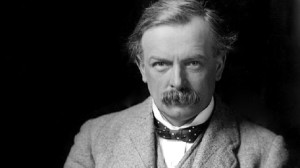

Ramsay MacDonald’s contemporary, David Lloyd George, was obliged to defend his reputation in court on more than one occasion. Few Victorian and Edwardian politicians were models of constancy. At some Cabinet meetings Prime Minister Herbert Asquith and one of his ministers would be occupied writing billet-doux to the same woman. L.G. – ‘the goat’ – was in a league of his own, however. ‘With an attractive woman he was as much to be trusted as a Bengal tiger with a gazelle,’ his son Dick observed in a biography of his father.

David Lloyd George in 1918

Prime Minister for the first time during the First World War, Lloyd George shared Number 10 with his wife and his mistress. He private secretary, Francis Stevenson, gave herself to him despite being twenty-three years younger. But he was no more faithful to his ‘Dear Pussy’ than he was to his wife. There were children with other women, abortions – Frances had two – a procession of disappointed lovers, outraged husbands, and at least one attempt to blackmail him. His sexual adventures were known and discussed in political circles and yet with clever lawyers and friends in the press he was able to avoid public disgrace.

So, too, the menage a trois involving Conservative Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, his wife and his parliamentary colleague Bob Boothby. After nine years of marriage and three children, Lady Dorothy Macmillan was introduced to handsome, rakish, sexually adventurous Boothby and the lives of all three were changed for ever. Macmillan refused to grant her a divorce even after she gave birth to his rival’s daughter. Divorce was out of the question: Macmillan loved his wife and the scandal would have destroyed both their careers. Instead they came to an arrangement that lasted until Dorothy’s death in 1966.

Harold and Dorothy Macmillan at their home Birch Grove

Lady Macmillan entered Number 10 with her husband in 1957 and played the part of a dutiful Prime Minister’s wife for five years. Not a word of her thirty year relationship with Boothby found its way into the papers. ‘Don’t let your boys hunt me down,’ Boothby pleaded with his friend, Beaverbrook, and sure enough the press baron held his reporters in check.

The deference shown to the private lives of politicians came to an end in a spectacular way in the last months of Macmillan’s premiership. ‘Sexual intercourse began in 1963,’ the poet, Philip Larkin observed in Annus Mirabilis . Newspapers began to serve sex at breakfast. It was the story with everything: a love triangle involving the minister for war, a Russian spy, and a call girl. John Profumo lied to parliament about his affair; Profumo had to go. The Prime Minister was in a terrible state, a Cabinet colleague recalled. The drip, drip coverage of the scandal over many weeks must have been painful for a man with a complicated sexual secret of his own to hide.

Politicians’ love lives have been treated as fair game in the sixty years since. Parliamentary ‘love cheats’ are pursued by photographers, pilloried on the front pages of the papers, and for a time those judged to have fallen short were in danger of committing political suicide. Harold Wilson kept his affair from reporters; John Major’s only made the papers after leaving Number 10. And now Boris Johnson has rewritten the rules. The coverage of his extra-marital liaisons, lurid stories of his sexual encounters, the speculation about the number of children he has fathered have only contributed to the image he has cultivated of a fun loving rogue. He is the first Prime Minister in more than a hundred years to have entered Number 10 not with his wife but with his lover. The sex lives of politicians will always make good copy but 21st century voters no longer view a colourful private life as a bar to high office.

Boris Johnson and Carrie Symonds outside Number 10

Ramsay MacDonald’s intermediary – Oswald Mosley – would probably have approved, since he despised the hypocrisy of the press and the ‘puritanism’ of his colleagues in parliament. Mosley considered his own love affairs to be healthy and necessary because – in the words of his son – ‘they gave him energy for the rigours of a life in politics’. Psychologists tell us that narcissism is rampant in politics and that many are the elected who consider themselves exceptional and free from the rules and standards that govern everyone else’s behaviour. ‘All his life he… fed on the love of those around him’, Richard Lloyd George observed of his Prime Minister father; ‘like a monster greedy child who demands everything.’ A monster greedy child – and the Prime Minister who won the First World War and laid the foundations of the welfare state. A certain type of political animal scrambles to the top of the greasy pole in politics.

Ramsay MacDonald in 1924

Ramsay MacDonald was committed – in his dead wife’s words – ‘to doing the work of our destiny’. He turned his back on his fifteen year affair with Margaret Sackville to put Labour’s cause first. He knew a Labour Prime Minister couldn’t count on the discretion of the press. ‘We have implacable enemies who sleeplessly lie in wait to damage our reputation’, he confided to his diary in January 1930. Confronted by the threat of an old lover to his premiership he turned to the one man in his ministry used to sloughing them off. Did Frau Forster really imagine a British government could be brought down by ‘one lonely woman’? Mosley asked her. ‘If you try to blackmail the Prime Minister he will be Mr X in court and you’ll go down for 10 or 20 years.’ He reduced her to tears. ‘Please, I want to leave, please don’t!’ she pleaded with him. And that, as far as Mosley was concerned, was the end of the Prime Minister’s affair. He was wrong, but that’s another story.

Click here to see Ramsay MacDonald introduce his 1929 Cabinet.