Front line officers and squaddies rarely have a good word to say for ‘brass hats’. ‘They were only playing leap frog’, soldiers of The Great War used to sing. Popular perceptions of headquarters staff have been influenced by that same squaddie jaundice, by class struggle, another war, by bad 1960’s history, and the poet’s ‘pity of war’, and by musicals, novels and television. In the comedy series ‘Blackadder Goes Forth’, bumbling and cowardly ‘red tabs’ send ordinary soldiers on pointless, suicidal missions. Two charges are constantly levelled at Field Marshal Haig and his Staff, namely that they were ignorant and unimaginative, and secondly, that they were out of touch with what was happening at the Front.

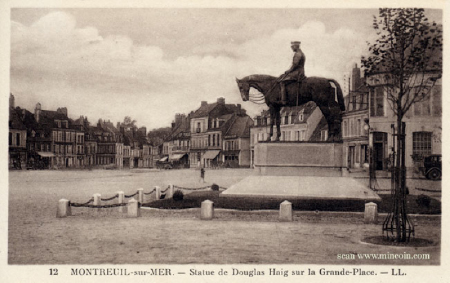

For most of the war, the British Army’s General Headquarters was more than forty miles from the line, in the small French town of Montreuil-sur-Mer in the Pas de Calais. Proof, Haig’s critics say, that the Field Marshal and his Staff were cut off from day to day life in the trenches. But as Britain’s commander-in-chief in France and Belgium he was responsible for nearly two million men and a Front of nearly a hundred miles. He conferred with French generals at Montreuil, and discussed strategy with Britain’s politicians and the leaders of her Empire. He was concerned with more than the day to day battle, but with plans for the next campaign, with the supply of men and munitions, with persuading Prime Minister and government that the war could only be won on the Western Front – by him. Montreiul was roughly equidistant from the furthest points of the British line.

The intelligence staff was accommodated in the old military school and billeted on the locals. An officer’s club opened at the end of 1917 but most GHQ departments eat in messes. Haig lived in a modest country house called the Chateau de Beaurepaire, a short distance from the town.

Beaurepaire today

There was no shortage of ‘red tabs’ at the Front, because both Haig’s armies in France and their divisions had staff operations of their own. Haig visited them regularly, and from 1917 he used a train as a mobile advanced headquarters.

The Staff at GHQ visited the Front, too, and far from being the shirkers of comedy myth, many, if not most, had served and been wounded in the line. One Staffer recalled in his memoirs the queue at the hospital in Montreuil, where officers struggling with old wounds went for treatment. GHQ was responsible for sifting and interpreting intelligence from many sources. Good communications with the Front were called for rather than close proximity. Brigadier Charteris’ officers visited it frequently, nonetheless.

GHQ intelligence staff. Major Stewart Menzies is standing second from the left, and Major James Marshall-Cornwell on the extreme right. Brigadier General Charteris is seated in the middle.

Of course, Staff life was comfortable by comparison with the lot of a Company commander and his men at the Front. Billets were warmer, beds were softer and cleaner, the food was a little better – but only a little – and, although the hours were generally longer, the Staffer could look forward to surviving the war. Encounters with the opposite sex were hard to come by because Haig disapproved of immoral behaviour at GHQ. French prostitutes enterprising enough to find their way to Montreuil were packed back on the train before they were able to corrupt the young men.

Staff Officers did lose their lives at the Front, and so did a surprising number of generals – more than two hundred. They were much closer to the Front than generals today. For more debunking of World War 1 myths, click through to the BBC’s myth busting website, written by TV historian, Dan Snow.