The hero of The Suicide Club served with the Queens Own Cameron Highlanders. Service on the Western Front has shaken his religious faith. But faith and the work of the army’s chaplains helped many endure the rigours of trench life.

Hard ground, hard rations, hard to imagine now perhaps that after so much suffering the soldiers of World War 1 could find comfort and hope and faith in the celebration of Christmas.

The famous Christmas story of the trenches is of the unofficial truce kept by both sides in the first year of the war. Barbed wire was hung with decorations, carols sung, and British and German soldiers met to exchange gifts of food, spirits and tobacco.

German and British soldiers in no-man’s-land 26th December 1914.

The senior officers of both sides didn’t share or approve of the brotherhood and cheer, and orders were issued in 1915 forbidding any further Christmas ‘fraternisation’. In the years that followed, front line officers issued their men with secret rum rations, there were hymns and parcels from home, but the fighting patrols, the sniping and the shelling carried on as always.

December 1918. Three Christmas’ later, the armies were still in the field but the war was over and the survivors could write their cards home confident they would live to celebrate another one. Up and down the line men thanked God for their deliverance and for victory. The military statisticians were still calculating the price: one million British and Empire dead, two million wounded.

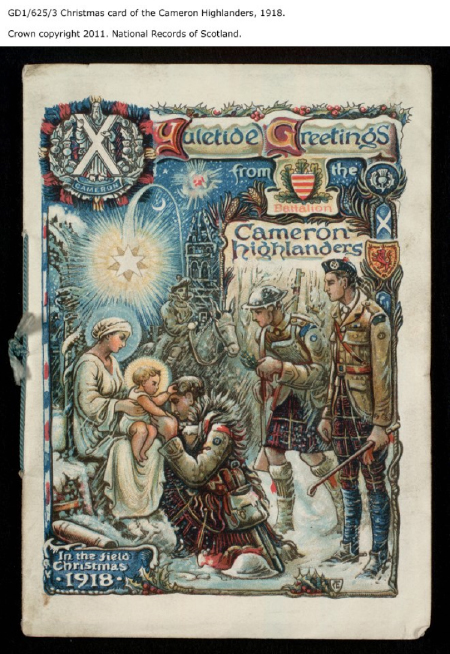

Christmas with the Camerons

An officer of the Cameron Highlanders sent this Christmas card from the old front to his friend, the Reverend William White Anderson, a senior military chaplain. The business of war is not forgotten by its soldier-artist: Mary is dressed in a nurse’s uniform, and a Highlander in an army winter warm bends like a shepherd to receive the blessing of the baby Jesus. The star that has brought these Camerons to the nativity has the trajectory of a whizz-bang and another explodes red in the sky to the right. There are no ox and ass in a stable but a soldier rides an artillery mule, and a fat piece of military ordnance is lying in something like a manager. In the background a church spire has been wrecked by shelling, but the soldier artist depicts comrades worshipping their Christ in the open, as if to make the point with simple piety that faith is strong in the field, even after all the sacrifice.

Battalion Christmas cards like this one were common at a time when soldiers were believers and many went to church. There were very few atheists in the trenches and in battle a prayer was never far from the lips.

Some soldiers and civilians on both sides beseeched their maker for victory. ‘God heard the embattled nations sing and shout’, the poet and historian J.C. Squire wrote in his satirical epigram of 1916; ‘‘Gott strafe England’ and ‘God save the King!’ God this, God that and God the other thing – ‘Good God!’ said God, ‘I’ve got my work cut out!’’

On the eve of the Somme, the Commander-in-Chief of the British armies, Field Marshal Haig wrote to his wife, ‘now you must know that I feel that every step in my plan has been taken with Divine help’. And his chaplain, the Reverend Duncan assured the congregation at British military headquarters that ‘nothing can withstand the prayers of a great united people’.

It was the sort of sentiment that went down badly with fighting men in the front line where military padres had a poor reputation. Good chaplains earned the right to preach by sharing the hardships and dangers of life in the line. Some of the best were moved to formations judged to be short on morale, where they distributed ‘fags’ and ‘love’ in equal measure. There were fewer prayers for victory and more ‘for the spirit of dogged perseverance and endurance’ to overcome fear. Men needed help with the mental scars of battle, they needed hope and they needed to believe something better would come of so much sacrifice. ‘If God spares us to return home’, the Reverend Victor Tanner told a battered battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment before the Christmas of 1917; ‘it must be our resolve to build a new England on the principles of righteousness, justice and brotherhood’. Survivors should honour the memory of the dead, he preached, by fighting to end ‘social injustice, luxury on the one hand and grinding poverty on the other, bad housing, immorality, class hatred and the like’. Britain must become, as Prime Minister Lloyd George put it in the Christmas of 1918, ‘a country fit for heroes’.

Something of that Christmas hope is expressed in the soldier artist’s image of the Cameron Highlander on his knees before the mother and child of the card.

Sandy, Innes, the hero of The Suicide Club volunteered for service with the 6th Battalion of the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders. Glasgow University Archive has a moving website telling the story of the students and lecturers who volunteered for the Camerons and of the part they played in the fighting at the Battle of Loos.